After the Liu family’s approval of our relationship, Joshua and I began telling our friends in church that we were a couple. Most of them were shocked. My roommates could not fathom what I saw in him because “he is so dark.” Many of my roommates were also very prejudiced against his Hakka subculture and told me that Hakka daughters-in-law were expected to work hard. I was not sure why they thought hard work would be a problem, and my friends’ views of Hakka families certainly did not match up to what I had seen when visiting the Liu family.

I had to renew my visa toward the end of February, and the clerk noted that I had thirteen months left on my passport. He urged me to look into options for renewing my passport because he had dealt with other Americans who had had trouble if they waited until they had less than six months left. I thanked him for the tip and went to the American Institute in Taiwan, a quasi-governmental agency that issues US visas and helps US citizens with services under the auspices of the American consulate in Hong Kong. The people at AIT told me that they were only authorized to renew passports of US citizens holding permanent residence status in Taiwan. So I began my quest for a “blue book”, the Taiwanese equivalent of a “green card.” Since I did simultaneous interpretation of church conferences from the back of the audience or from a translation booth instead of standing beside the speaker on the pulpit, I did not qualify for a religious visa. I was not a real “minister.” The church publishing company was five employees short of qualifying to hire me as a foreign specialist and getting me a “blue book.” The only avenue left was for me to marry a Taiwanese citizen.

Liu Yuni and I met with the church elders about a church wedding as soon as possible. And their answer was a resounding, “No!” The elders reasoned that our family backgrounds were too different and that my parents had not yet met my prospective groom. They were sure that my parents would not approve of my marrying someone engaged in physical labor or a professional trade. They were convinced that my parents would forbid me to marry into a family where my in-laws had so little education. They told us that they could not stop us from having a court wedding, but if we wanted the church to bless our marriage, we needed approval from both sets of parents. And they thought that Liu Yuni should be finished with his mandatory tour of military duty before we even considered marriage. They told me to renew my passport over the summer when I went home for a visit. I told them that according to the people at AIT, I would need to stay in the US and pay taxes for a year before I would be eligible to do that. The elders did not believe that the workers at AIT properly represented the US government, and they were sure I would have no problems once I arrived in the US.

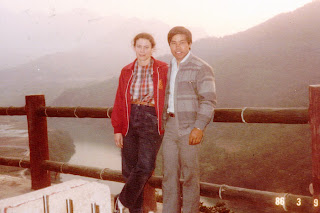

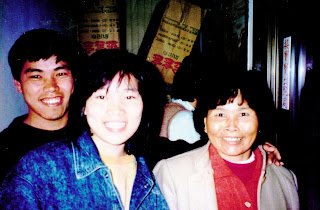

When we mentioned the church elders’ concerns to Mr. Liu, he agreed that he would feel better about the marriage if my parents got to meet his family and his son first. He also wanted to spend time with me discussing my views on supporting aging parents-in-law and on funeral rites and honoring dead ancestors. So Liu Yuni took a leave of absence from his last semester in school and signed up to immediately begin his military tour of duty. By mid-March, he was inducted to the army and sent to Ilan for three months of basic training. I called home several times about the situation. At first, my entire family was planning to come for an April wedding during my brother’s spring break from vet school. After the church’s opposition, they cancelled their plane reservations, and my mother decided to come in May for my twenty-fifth birthday and to meet her potential son-in-law.

Every weekend I would either take the train by myself to the military base in Ilan to visit Liu Yuni, or I would ride with the Liu family when they all went to see him. Mr. Liu kept me in the front of the truck on those rides, and we discussed the all-important issue of filial piety. I later learned that the extended family had told him stories about American families and how American children allowed elderly parents to die in poverty or even charged them for rent or elder care. Mr. Liu wanted to know about my parents’ relationships with my grandparents and my grandparents’ relationships with my great-grandparents. He was quite relieved to learn that my grandparents on both sides of the family had taken aging great-grandparents into their homes and cared for them for years without charging them rent or nursing fees. I was shocked that people would think such things about Americans. He asked me how much money I contributed to the support of my parents every month. I responded that they made so much money that they didn’t need or want my support. I also told him about Teacher Chin’s Chinese daughter-in-law lessons and that I understood the dynamics and structure of Chinese families.

So our conversation turned to funerals and worshipping ancestors. Mr. Liu had been very impressed as a young man at Chiang Kai-shek’s state funeral. Madame Chiang had not allowed the masses who crowded the route of Chiang Kai-shek’s funeral cortege to burn incense in worship of him because the family was Christian. Instead, she asked that everyone throw flowers, and she asked people of all faiths to pray for blessings on the country in Chiang’s memory. In my description of US funerals I had been to, I told Mr. Liu that there were prayers for the dead person’s soul, that people shared their memories of the person’s life, and that frequently the funeral ended with prayers for the rest of the person’s family. He was very interested in the funeral flowers. I told him that most people sent arrangements of flowers and that sometimes the mourners or family members would file past the casket and place flowers on it or throw flowers into the grave. I also told him that in many families, the family members would regularly place fresh flowers on the person’s grave. In the end, we arrived at an understanding. If I married into his family, my children and I would be exempt from burning incense to the Liu ancestors, but we would be expected to purchase and present large wreaths at funerals. During the funeral ceremonies, we would have to stand before the casket with our heads bowed in prayer for the entire Liu family after we had presented our wreaths. We would wear the traditional funeral attire and march in the funeral procession according to our rank in the family. We would not participate in the traditional tomb sweeping activities when everyone else was burning incense, but either before or after, we would go up to the tomb, pray to the Christian God for the Liu family, and place flowers on the family tomb.

With these crucial matters settled, Mr. Liu became a strong advocate of our marriage. The church leaders who personally knew Liu Yuni also agreed that we were well-matched in temperament. But we still had to convince the ones who could only see the outward differences in culture and social status. I told them that I wanted to marry someone with much darker skin than mine, so my children would be less likely to get painful sunburns. I told them that I looked at a person’s character and natural intelligence more than his or her level of education and social rank. The members of the Liu family are all very bright and of generally good character. I also told them that money came and went easily. I was not really worried about the family’s finances. Nor was I afraid of hard work. I was impressed with the industriousness of all the Lius, and I believed (correctly) that their financial setbacks were temporary. Nevertheless, I was again inundated with a flood of potential suitors that church matchmakers felt were more “suitable” prospects. Their attitudes made me pretty angry, but I figured the best thing was to wait for my mom’s visit, since I wouldn’t get anywhere without my own parents’ approval of the match.

I had to renew my visa toward the end of February, and the clerk noted that I had thirteen months left on my passport. He urged me to look into options for renewing my passport because he had dealt with other Americans who had had trouble if they waited until they had less than six months left. I thanked him for the tip and went to the American Institute in Taiwan, a quasi-governmental agency that issues US visas and helps US citizens with services under the auspices of the American consulate in Hong Kong. The people at AIT told me that they were only authorized to renew passports of US citizens holding permanent residence status in Taiwan. So I began my quest for a “blue book”, the Taiwanese equivalent of a “green card.” Since I did simultaneous interpretation of church conferences from the back of the audience or from a translation booth instead of standing beside the speaker on the pulpit, I did not qualify for a religious visa. I was not a real “minister.” The church publishing company was five employees short of qualifying to hire me as a foreign specialist and getting me a “blue book.” The only avenue left was for me to marry a Taiwanese citizen.

Liu Yuni and I met with the church elders about a church wedding as soon as possible. And their answer was a resounding, “No!” The elders reasoned that our family backgrounds were too different and that my parents had not yet met my prospective groom. They were sure that my parents would not approve of my marrying someone engaged in physical labor or a professional trade. They were convinced that my parents would forbid me to marry into a family where my in-laws had so little education. They told us that they could not stop us from having a court wedding, but if we wanted the church to bless our marriage, we needed approval from both sets of parents. And they thought that Liu Yuni should be finished with his mandatory tour of military duty before we even considered marriage. They told me to renew my passport over the summer when I went home for a visit. I told them that according to the people at AIT, I would need to stay in the US and pay taxes for a year before I would be eligible to do that. The elders did not believe that the workers at AIT properly represented the US government, and they were sure I would have no problems once I arrived in the US.

When we mentioned the church elders’ concerns to Mr. Liu, he agreed that he would feel better about the marriage if my parents got to meet his family and his son first. He also wanted to spend time with me discussing my views on supporting aging parents-in-law and on funeral rites and honoring dead ancestors. So Liu Yuni took a leave of absence from his last semester in school and signed up to immediately begin his military tour of duty. By mid-March, he was inducted to the army and sent to Ilan for three months of basic training. I called home several times about the situation. At first, my entire family was planning to come for an April wedding during my brother’s spring break from vet school. After the church’s opposition, they cancelled their plane reservations, and my mother decided to come in May for my twenty-fifth birthday and to meet her potential son-in-law.

Every weekend I would either take the train by myself to the military base in Ilan to visit Liu Yuni, or I would ride with the Liu family when they all went to see him. Mr. Liu kept me in the front of the truck on those rides, and we discussed the all-important issue of filial piety. I later learned that the extended family had told him stories about American families and how American children allowed elderly parents to die in poverty or even charged them for rent or elder care. Mr. Liu wanted to know about my parents’ relationships with my grandparents and my grandparents’ relationships with my great-grandparents. He was quite relieved to learn that my grandparents on both sides of the family had taken aging great-grandparents into their homes and cared for them for years without charging them rent or nursing fees. I was shocked that people would think such things about Americans. He asked me how much money I contributed to the support of my parents every month. I responded that they made so much money that they didn’t need or want my support. I also told him about Teacher Chin’s Chinese daughter-in-law lessons and that I understood the dynamics and structure of Chinese families.

So our conversation turned to funerals and worshipping ancestors. Mr. Liu had been very impressed as a young man at Chiang Kai-shek’s state funeral. Madame Chiang had not allowed the masses who crowded the route of Chiang Kai-shek’s funeral cortege to burn incense in worship of him because the family was Christian. Instead, she asked that everyone throw flowers, and she asked people of all faiths to pray for blessings on the country in Chiang’s memory. In my description of US funerals I had been to, I told Mr. Liu that there were prayers for the dead person’s soul, that people shared their memories of the person’s life, and that frequently the funeral ended with prayers for the rest of the person’s family. He was very interested in the funeral flowers. I told him that most people sent arrangements of flowers and that sometimes the mourners or family members would file past the casket and place flowers on it or throw flowers into the grave. I also told him that in many families, the family members would regularly place fresh flowers on the person’s grave. In the end, we arrived at an understanding. If I married into his family, my children and I would be exempt from burning incense to the Liu ancestors, but we would be expected to purchase and present large wreaths at funerals. During the funeral ceremonies, we would have to stand before the casket with our heads bowed in prayer for the entire Liu family after we had presented our wreaths. We would wear the traditional funeral attire and march in the funeral procession according to our rank in the family. We would not participate in the traditional tomb sweeping activities when everyone else was burning incense, but either before or after, we would go up to the tomb, pray to the Christian God for the Liu family, and place flowers on the family tomb.

With these crucial matters settled, Mr. Liu became a strong advocate of our marriage. The church leaders who personally knew Liu Yuni also agreed that we were well-matched in temperament. But we still had to convince the ones who could only see the outward differences in culture and social status. I told them that I wanted to marry someone with much darker skin than mine, so my children would be less likely to get painful sunburns. I told them that I looked at a person’s character and natural intelligence more than his or her level of education and social rank. The members of the Liu family are all very bright and of generally good character. I also told them that money came and went easily. I was not really worried about the family’s finances. Nor was I afraid of hard work. I was impressed with the industriousness of all the Lius, and I believed (correctly) that their financial setbacks were temporary. Nevertheless, I was again inundated with a flood of potential suitors that church matchmakers felt were more “suitable” prospects. Their attitudes made me pretty angry, but I figured the best thing was to wait for my mom’s visit, since I wouldn’t get anywhere without my own parents’ approval of the match.