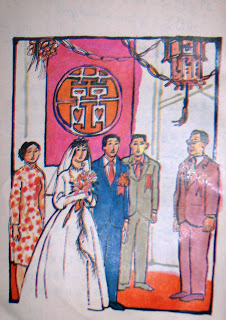

Soon we had finished the book of moral tales and moved into Teacher’s favorite intermediate book: Chinese Customs and Traditions. The lessons in this book were essays on different aspects of Chinese life and culture. They covered topics like Chinese New Year, Tomb-sweeping Festival, Dragon Boat Festival, Eating, Kung-fu, Houses, Friendships, Filial Piety, Funerals, Temple Festivals, Family Relationships, and of course, “The Greatest Event in Life: Marriage”. Teacher promised us that by the time we finished this book, our thinking and concepts would be partially Chinese. We spent at least nine months going through all the lessons. One of the lessons that took us the longest to finish to Teacher’s satisfaction was the unit on marriage. I have translated it here in its entirety. The pictures show the text and illustrations.

The Greatest Event in Life

Chinese people call marriage the greatest event in life. Because the Chinese have such a strong concept of family ties, they believe that ruling one’s family is the basis of a stable society and a peaceful world. The ancient Chinese continually told their scholars that if they wanted to govern the country, they must first rule their homes well. For this reason, the Chinese do not merely consider a marriage to be the union between a man and a woman, but also they see marriage as the foundation of society. It is a solemn matter that cannot be accomplished lightly.

In traditional Chinese marriage, one did not choose one’s own partner; instead, the heads of the households made the decisions, and marriages were accomplished through the introductions of a matchmaker. According to ancient records, there were six steps to a marriage. The first step was called “presenting betrothal gifts.” In this step, the man’s family presented the woman’s family with a small gift (a wild goose) to express their wish to negotiate a marriage. The second step was called “asking the names.” In this step, the man’s family asked for a clear accounting of the woman’s names and relations, so that they could cast the horoscopes. The third step was “divining the luck”. In this step the man’s family divined the good or bad fortune of the marriage and then brought gifts to the woman’s family to report the good news. The fourth step was “presenting betrothal gifts”, and this was the same as an engagement. Of course, in this stage, a larger gift was given. The fifth step was called “selecting the date,” and in this stage the most auspicious day for the wedding was determined, and the consent of the woman’s family was sought for that date. The sixth step was called “escorting the bride,” and that was the wedding ceremony. These six steps are called the “six rites.”

Nowadays the rites are much simpler. People choose their own spouses, but they still ask for their parents’ permission. Then they set the wedding date and send invitations to their friends and relatives, inviting them to the wedding ceremony and the wedding feast. Now the most popular wedding ceremonies are simple and elegant. Some people are married in churches, and others get married in civil ceremonies at court; still others are married in group weddings.

Old style weddings had another step called “joking in the bridal chamber.” Within the first three days after the wedding, anyone—male, female, old, and young—was allowed to make jokes with the bride and bridegroom. The goal of this custom was to allow the bride and groom, who had never met before the wedding, to get to know each other in a light, relaxed atmosphere. This custom still exists today in a limited fashion.

The textbook essay is wrong in saying that the six rites are no longer used. While the first gift is no longer a wild goose and the matchmakers are usually elderly friends or relatives, the six rites live on today, especially among working class, farming, and illiterate social groups. There are regional variations and rituals for each step, but I would say that the six rites continue to be used even today among many of my Chinese relatives and friends. The last wedding we attended that used these customs was on April 26, 2007, in New York City among friends from a group of Chinese expatriates from Fuzhou. Last month, a cousin of the 2007 groom went through the same six steps for his own wedding just before Chinese New Year. The going bride price in the Fuzhou restaurant-owning community is $36,000 (US dollars). I am used to the idea of bride prices and trousseaus now, but when the time came for my Chinese wedding I would not allow my father to ask for money from Joshua’s family. The depths of my little American soul were horrified at the idea of being bought or sold. Eventually, I sat in on some negotiations concerning marriages for my husband’s siblings because I was the eldest daughter-in-law. Then, I began to understand more of the traditional Chinese concepts of marriage, and I was better able to understand what my teacher had been talking about.