My grandparents: Philo and Nellie Zimmerman and John and Margaret Ryder. June, 1960 at my parents wedding, 11 months before I was born.

My grandparents: Philo and Nellie Zimmerman and John and Margaret Ryder. June, 1960 at my parents wedding, 11 months before I was born.

The Zimmerman side Great-Grandparents with my parents: Gramps and Grammie Heritage and Grandma Z.

The Ryder side Great-Grandparents: Grandma Ryder and Kelly (Margaret Kelly Dyer) with my parents Anne Ryder and Gary Zimmerman

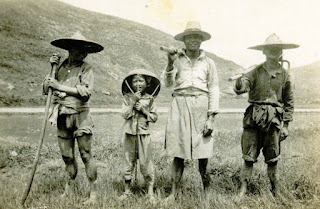

Grandpa John Ryder's Pictures of China in the 1920's when he worked on a China trading ship

Village with canal near Haining

Temple at Lin Ying, Hangchow

I once read that culture is contained in the stories passed from one generation to the next, but I never understood what that meant until I began reminiscing about my intermediate Chinese classes for this blog. The major part of every class at the intermediate level was spent either listening to Teacher tell us the stories from her childhood or repeating and rewriting the stories until they became ours. All of Teacher’s stories had a message, and each story was told with the goal of helping us enter into Chinese cultural patterns of thought.

During my intermediate Chinese classes, my mind became a battlefield of dueling stories. There was an internal struggle between the American concepts of my psychological constitution, and the Chinese concepts I was trying to learn. This post is a digression from the story of my life in Taiwan because I want to share the stories from my childhood that define the American core of my being. These stories may not be entirely accurate as to the facts, but this is what I believed about my heritage after listening to adult family members during my childhood.

My own family has been in America since 1775, when my ancestor Joseph Zimmerman emigrated here from Germany. A later Zimmerman was an officer in the War of 1812. The main story that I got from the Zimmerman side of the family was that we have deep American roots. My Grammie Zimmerman was a Daughter of the Revolution and came from another old, established American family. Gramps Zimmerman grew up as the son of a bookkeeper in a logging camp near Oswego, Oregon. He was brilliant at Math and graduated from university Phi Beta Kappa. Gramps passed the CPA exam on his first try and made a killing in the stock market long before I was born. He was semi-retired by the time I had memories of him. Grammie Zimmerman was the perfect business wife. She could single-handedly put out a homemade multi-course dinner for one hundred people and serve it with formal settings, polished silver, etc. My dad was their elder son. He graduated from Cal Tech, went on to get a PhD in Chemistry and was active in developing the field of Clinical Chemistry. One of my daughter’s friends recently saw an old picture of him at our house and asked why a person from her chemistry textbook graced our bookshelves. I had not even been aware that Dad was so well-known in the field. Understated excellence was expected in the Zimmerman family. Education was important, and we came out of college debt-free, but then there was a strong expectation that we would take that education and training to make something of ourselves. Zimmermans are expected to excel almost as a matter of course, but they are also expected to be modest, self-effacing, and keep a stiff upper lip.

My mom’s family, the Ryders, also arrived in North America before the Revolution. They were sea captains in Nova Scotia and did not come to the United States until much later. My Grandpa Ryder’s father and his older brother died when Grandpa was quite young. He became the man of the house doing several jobs from the time he was eleven to support his mother, younger brother and sisters. He delivered milk before school and drove a trolley after class. He spent some time working on a ship and posthumously contributed the pictures of China at the beginning of this post. Eventually, he began to work at a bank and over the course of his career went from teller to Executive Vice President. Grandpa Ryder was one of an extinct breed: an honorable politician. He served in the State Legislature for twenty years and was respected by everyone on both sides of the aisle for his integrity and straight-dealing. He was close to the Governor of Washington and the US Senators from the state when we were growing up. It was not uncommon for my brother and me to come in contact with the leaders of Washington State when we visited Grandpa.

My Grandma Ryder also had a hard life. Her father died when Grandma was five, and her mother, my Great-Grandma Margaret Kelly Dyer, raised her two daughters single-handedly. Kelly lived to be 101 years old, and I was 17 when she finally passed away. Kelly was the first white child born in O’Neal County, Nebraska. She was the eldest of 13 children in a large Irish pioneer family. She told me numerous stories about taming horses with her father, interacting with the Native Americans, leaving home to work as a seamstress so her younger siblings would have enough to eat, and moving to Montana with her sisters to run a boarding house for miners. My mother absorbed the Ryder ethic of fighting to overcome adversity and attain one’s goals in life. Mom competed for and won a scholarship to Radcliffe College (women’s adjunct to Harvard University) where she did really well in her studies. When I was eight she went back for a Master’s and had several successful careers as a librarian, lobbyist, and finally a lawyer.

Both the Ryders and the Zimmermans advocated personal excellence first and foremost; then they expected family members to use their talents for the common good without taking too much credit. There were also strong themes of individual integrity and overcoming all obstacles to make good. My parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles were leaders in the Seattle community and even in the State of Washington, but the sense I got was that their prominence did not give us a free ride. My brother and I would get an excellent education and introductions to movers and shakers, who could possibly advance our careers, but we had to work hard and earn our own way in the world. I do not know if it was intentional, but I always got the sense that I would not be considered a true success until I had found some adversity to overcome as my elders had before me. The way success was achieved was also as important as the act of succeeding. Honor, integrity, lawfulness, and working for the common good got top billing in our family’s traditions.

There were common threads between my core stories and the core Chinese stories that Teacher told us, but at certain crucial points, the stories were almost diametrically opposite. Learning Chinese fluently required me to frequently accept concepts that were very different from my own worldview.

During my intermediate Chinese classes, my mind became a battlefield of dueling stories. There was an internal struggle between the American concepts of my psychological constitution, and the Chinese concepts I was trying to learn. This post is a digression from the story of my life in Taiwan because I want to share the stories from my childhood that define the American core of my being. These stories may not be entirely accurate as to the facts, but this is what I believed about my heritage after listening to adult family members during my childhood.

My own family has been in America since 1775, when my ancestor Joseph Zimmerman emigrated here from Germany. A later Zimmerman was an officer in the War of 1812. The main story that I got from the Zimmerman side of the family was that we have deep American roots. My Grammie Zimmerman was a Daughter of the Revolution and came from another old, established American family. Gramps Zimmerman grew up as the son of a bookkeeper in a logging camp near Oswego, Oregon. He was brilliant at Math and graduated from university Phi Beta Kappa. Gramps passed the CPA exam on his first try and made a killing in the stock market long before I was born. He was semi-retired by the time I had memories of him. Grammie Zimmerman was the perfect business wife. She could single-handedly put out a homemade multi-course dinner for one hundred people and serve it with formal settings, polished silver, etc. My dad was their elder son. He graduated from Cal Tech, went on to get a PhD in Chemistry and was active in developing the field of Clinical Chemistry. One of my daughter’s friends recently saw an old picture of him at our house and asked why a person from her chemistry textbook graced our bookshelves. I had not even been aware that Dad was so well-known in the field. Understated excellence was expected in the Zimmerman family. Education was important, and we came out of college debt-free, but then there was a strong expectation that we would take that education and training to make something of ourselves. Zimmermans are expected to excel almost as a matter of course, but they are also expected to be modest, self-effacing, and keep a stiff upper lip.

My mom’s family, the Ryders, also arrived in North America before the Revolution. They were sea captains in Nova Scotia and did not come to the United States until much later. My Grandpa Ryder’s father and his older brother died when Grandpa was quite young. He became the man of the house doing several jobs from the time he was eleven to support his mother, younger brother and sisters. He delivered milk before school and drove a trolley after class. He spent some time working on a ship and posthumously contributed the pictures of China at the beginning of this post. Eventually, he began to work at a bank and over the course of his career went from teller to Executive Vice President. Grandpa Ryder was one of an extinct breed: an honorable politician. He served in the State Legislature for twenty years and was respected by everyone on both sides of the aisle for his integrity and straight-dealing. He was close to the Governor of Washington and the US Senators from the state when we were growing up. It was not uncommon for my brother and me to come in contact with the leaders of Washington State when we visited Grandpa.

My Grandma Ryder also had a hard life. Her father died when Grandma was five, and her mother, my Great-Grandma Margaret Kelly Dyer, raised her two daughters single-handedly. Kelly lived to be 101 years old, and I was 17 when she finally passed away. Kelly was the first white child born in O’Neal County, Nebraska. She was the eldest of 13 children in a large Irish pioneer family. She told me numerous stories about taming horses with her father, interacting with the Native Americans, leaving home to work as a seamstress so her younger siblings would have enough to eat, and moving to Montana with her sisters to run a boarding house for miners. My mother absorbed the Ryder ethic of fighting to overcome adversity and attain one’s goals in life. Mom competed for and won a scholarship to Radcliffe College (women’s adjunct to Harvard University) where she did really well in her studies. When I was eight she went back for a Master’s and had several successful careers as a librarian, lobbyist, and finally a lawyer.

Both the Ryders and the Zimmermans advocated personal excellence first and foremost; then they expected family members to use their talents for the common good without taking too much credit. There were also strong themes of individual integrity and overcoming all obstacles to make good. My parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles were leaders in the Seattle community and even in the State of Washington, but the sense I got was that their prominence did not give us a free ride. My brother and I would get an excellent education and introductions to movers and shakers, who could possibly advance our careers, but we had to work hard and earn our own way in the world. I do not know if it was intentional, but I always got the sense that I would not be considered a true success until I had found some adversity to overcome as my elders had before me. The way success was achieved was also as important as the act of succeeding. Honor, integrity, lawfulness, and working for the common good got top billing in our family’s traditions.

There were common threads between my core stories and the core Chinese stories that Teacher told us, but at certain crucial points, the stories were almost diametrically opposite. Learning Chinese fluently required me to frequently accept concepts that were very different from my own worldview.

4 comments:

I am here via Chris. Very interesting stories. It is so interesting to hear about living in different cultures. What an adventure! I will be back to poke around some more.

Hi Debra,

Welcome to the blog. I will get to some of the stories I mentioned on Chris's blog by summer time.

Teresa

Definitely look like your mother in her bridal picture.

How interesting that your grandfather had his own China connection.

The oral/storytelling aspect to Teacher Chin's pedagogy is very interesting, and the confidence with which she universalized her own life as a structure for her students. My therapy mentor in graduate school would often say that we should do things his way, until we felt the confidence to break free into our own ways of being. I loved him as a father, and it was interesting when I finally did break free into, in some ways, a very different clinician. Though he passed years ago, I still feel him at the core of who I am today.

When I first began teaching, my style was very much like Teacher Chin's. It gradually evolved into something that was more "me", especially after I came to America and had to deal with different expectations from students, but at some core level, I internalized her values of wanting to lay a solid foundation for my students.

Post a Comment