">

">

Sunday, September 27, 2009

Saturday, September 26, 2009

A Passion for Teaching

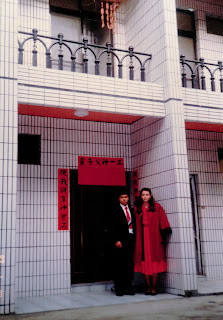

The owners and Chinese TAs at the night market branch of the Gloria English School

In March or April I began teaching two days a week at the Gloria English School in Chungli and Taoyuan. When I was teaching in Taipei, I taught adult conversation and beginning composition to people who were planning to take the TOEFL exam to come to the US and study. Many of the students came late after work, and most of them had not done any homework, so the classes moved slowly. Things at the Gloria English School were very different.

The Gloria English School was an afterschool “cram school” that taught English to children from preschool up through the end of high school. It used the English books from Singapore’s elementary school curriculum, and then the school added its own touches like songs, basic conversation, games, and “direct phonics.” Instead of teaching the KK phonetic system like Taiwan’s junior high schools, the Gloria English School taught the alphabet with phonics. This helped the students with pronunciation and reading.

Each class met for two hour sessions twice a week. The class had an American teacher and a Chinese teacher. The Chinese teacher acted as TA when the American was there one day a week, and then she would explain the points of grammar and review the lessons on the second day. The Americans spent two hours a week with each class.

All the elementary schools were in session for only a half day on Wednesday and Saturday, so the school ran classes all afternoon and evening. Classes started around 5 pm the other days of the week, and the schools were closed on Sundays. I was given classes on Tuesday and Friday evenings to start with. I only worked half days in Taipei on those days so I could get back in time for the classes.

They were so much fun. Most classes had a row of mothers in the back learning English with their children. We would come in, review the previous lesson, sing whatever songs I wanted to teach them, play some games to review grammar, and then learn a new lesson. The mothers took notes on what homework had been assigned, and the students usually did it all. The parents were paying quite a bit of money to have their children taught by real Americans, and they made sure that the kids got the most of the opportunity. The method of teaching was fun, too. Every concept was practiced through contests and games. At first it seemed that we were moving more slowly than the other schools (Big Bird’s English, for example), but because we had six books to our curriculum, our students were able to stay with us for a long time. By the time they got to the later books, they spoke, read, and wrote very good English. Many of them won English competitions in speaking and writing when they were in high school.

I thoroughly enjoyed the classes. It was like I was playing word games for several hours a day, and I was getting paid big bucks to do it!! The students and parents liked me, so as my classes in Taipei ended, I added more and more evenings in Chungli. Over the summer, the owners of GES (who were also Hakka) decided to give me classes for nine hours a day, five days a week. By this time, I was feeling the pressure of the monthly mortgage payments, so I immediately accepted. I quit my job with the church publishing company and became a full-time English teacher.

For the most part the morning classes in the summer were for new students. They met five days a week, and we were supposed to teach the entire alphabet, phonetic reading, fifteen songs, and enough conversation for the students to be able to introduce themselves in English by the end of the 8 week course. Since they were coming daily, they only met for an hour a day. We had to keep everything fast-paced and fun because we needed these students to make up our classes during the school year. The goal of summer session was to make them fall in love with learning English. In general, my classes had a high retention rate.

When I started, GES had three branches: two in Chungli and one in Taoyuan to the North. I was in Taoyuan for two days a week and in Chungli for three days. Some days in Chungli, I would be at the branch near the train station in the morning and have to rush to the branch near the night market in the afternoon. Eventually, Pa Liu decided that I should learn to ride a 50 cc motor scooter, so I could get to classes on time. When I went to Taoyuan, I took the bus to the train station and took the train, but when I was in Chungli, I puttered along on the family’s little red scooter. I did not need to take a licensing test because before our honeymoon, I had gotten a reciprocal license to drive a car with my regular US driver’s license. That was all I needed to drive a 50 cc motor bike. Life got easier for Pa and Yuntian, too, because they only needed to pick me up at the train station two nights a week, and since I was teaching children, the classes ended earlier.

Over my three year stay with GES, they eventually expanded to five branches all in the Chungli and Taoyuan area. They even got the contract to teach English to the flight attendants for the new Evergreen Airlines. And after we came to the US, I organized two cultural exchanges for GES students. They came to the US and did some touring, then I took them to a school or summer camp to meet and mingle with American kids. Working at that school was one of the best jobs I ever had.

The Gloria English School was an afterschool “cram school” that taught English to children from preschool up through the end of high school. It used the English books from Singapore’s elementary school curriculum, and then the school added its own touches like songs, basic conversation, games, and “direct phonics.” Instead of teaching the KK phonetic system like Taiwan’s junior high schools, the Gloria English School taught the alphabet with phonics. This helped the students with pronunciation and reading.

Each class met for two hour sessions twice a week. The class had an American teacher and a Chinese teacher. The Chinese teacher acted as TA when the American was there one day a week, and then she would explain the points of grammar and review the lessons on the second day. The Americans spent two hours a week with each class.

All the elementary schools were in session for only a half day on Wednesday and Saturday, so the school ran classes all afternoon and evening. Classes started around 5 pm the other days of the week, and the schools were closed on Sundays. I was given classes on Tuesday and Friday evenings to start with. I only worked half days in Taipei on those days so I could get back in time for the classes.

They were so much fun. Most classes had a row of mothers in the back learning English with their children. We would come in, review the previous lesson, sing whatever songs I wanted to teach them, play some games to review grammar, and then learn a new lesson. The mothers took notes on what homework had been assigned, and the students usually did it all. The parents were paying quite a bit of money to have their children taught by real Americans, and they made sure that the kids got the most of the opportunity. The method of teaching was fun, too. Every concept was practiced through contests and games. At first it seemed that we were moving more slowly than the other schools (Big Bird’s English, for example), but because we had six books to our curriculum, our students were able to stay with us for a long time. By the time they got to the later books, they spoke, read, and wrote very good English. Many of them won English competitions in speaking and writing when they were in high school.

I thoroughly enjoyed the classes. It was like I was playing word games for several hours a day, and I was getting paid big bucks to do it!! The students and parents liked me, so as my classes in Taipei ended, I added more and more evenings in Chungli. Over the summer, the owners of GES (who were also Hakka) decided to give me classes for nine hours a day, five days a week. By this time, I was feeling the pressure of the monthly mortgage payments, so I immediately accepted. I quit my job with the church publishing company and became a full-time English teacher.

For the most part the morning classes in the summer were for new students. They met five days a week, and we were supposed to teach the entire alphabet, phonetic reading, fifteen songs, and enough conversation for the students to be able to introduce themselves in English by the end of the 8 week course. Since they were coming daily, they only met for an hour a day. We had to keep everything fast-paced and fun because we needed these students to make up our classes during the school year. The goal of summer session was to make them fall in love with learning English. In general, my classes had a high retention rate.

When I started, GES had three branches: two in Chungli and one in Taoyuan to the North. I was in Taoyuan for two days a week and in Chungli for three days. Some days in Chungli, I would be at the branch near the train station in the morning and have to rush to the branch near the night market in the afternoon. Eventually, Pa Liu decided that I should learn to ride a 50 cc motor scooter, so I could get to classes on time. When I went to Taoyuan, I took the bus to the train station and took the train, but when I was in Chungli, I puttered along on the family’s little red scooter. I did not need to take a licensing test because before our honeymoon, I had gotten a reciprocal license to drive a car with my regular US driver’s license. That was all I needed to drive a 50 cc motor bike. Life got easier for Pa and Yuntian, too, because they only needed to pick me up at the train station two nights a week, and since I was teaching children, the classes ended earlier.

Over my three year stay with GES, they eventually expanded to five branches all in the Chungli and Taoyuan area. They even got the contract to teach English to the flight attendants for the new Evergreen Airlines. And after we came to the US, I organized two cultural exchanges for GES students. They came to the US and did some touring, then I took them to a school or summer camp to meet and mingle with American kids. Working at that school was one of the best jobs I ever had.

Saturday, September 19, 2009

First Chinese New Year with the Lius

In heels and a dress playing on a rope bridge at the park. I have truly gone native!

Out rowing on the lake.

With Liu Yuni's cousins at the Liu family tomb.

Two weeks after we moved into the new house, it was the Chinese New Year. All my friends in Taipei were from the church, and they did not adhere strictly to many of the Chinese New Year traditions. In the Liu household, only Yuni, Hsiu-Chu, and I were practicing Christians, so especially that first year, they did all the ceremonies. The first thing was to clean the house from top to bottom on Chinese New Year’s Eve. That part wasn’t too hard since it was a new house, but they did work hard to get everything unpacked and put away neatly. They also laid in lots of food because the markets would be closed for several days. Then they made rice flour cakes. Later, they stopped making these by hand, but the first year in our new house, they did everything according to tradition.

All the unmarried girls and Yuni got to come home for New Year’s Eve dinner. We all ate together at the round dining table. There was a big bowl of fish soup, but we were only supposed to take a taste and leave the rest, so there would be plenty in the New Year. We had red couplets beside the doorway praying for blessings on the household. Yuni and I got one of our friends from church to write them, so they were Christian poems. They were actually quite nice, and Pa Liu was pleased that they were hand-written in nice calligraphy instead of just store-bought ones.

We all went to bed, but Ma and Pa and Hsiu-Mei, Hsiu-Chen, and Yuntian got up in the middle of the night to offer a whole boiled chicken to the ancestors and to set off firecrackers. I was just as happy not to have to get out from under my warm blankets because it was chilly. The next day we all had to wear red, new clothes. I just wore my red wedding dress from the church ceremony because I didn’t want to buy yet another red dress. Yuni wore his suit from the wedding, too. We ate sweet rice cake and fruit and watermelon seeds. Then we all went out to a park for a day at the lake. We were all dressed up for it, too. Then we came home and cleaned up for the next day when the married daughters would come home.

Traditionally, married daughters come home on the second day of the Chinese New Year. Yuni should have taken me to visit my parents, but he was back at his military unit, and it would not have been feasible for me to fly back to the US. So instead, I made waffles for everyone for breakfast. Elder Sister and Elder Brother-in-Law and their four daughters arrived bright and early the next morning. They all loved the waffles. (My relatives had given me a waffle iron for my wedding, and I had a cookbook with a recipe for homemade waffles.) We kept waiting and waiting for Youngest Sister and her husband. Finally, we got a phone call that her mother-in-law was not going to allow her to come unless the Lius guaranteed that she and I would not see each other face to face while she was here.

I knew that the Liu family was worried about her being pregnant with a broken leg, so I said that I would stay upstairs in my third floor rooms. They all thanked me profusely, and I went up to read. Yuntian later came up with a small tv and VCR and a pile of kung-fu movie videos. He also kept bringing food up for me in case I was hungry. I hung over the top of the house and watched her arrive (darting back before anyone saw me, of course.) Since Youngest Sister (Hsiu-ling) had a broken leg she could not go out anywhere. She just sat at home with her mother and one or two of her sisters while her husband and the rest of the entire group took Elder Sister’s children to a park. I unpacked more of my books from America, read Hawaii, watched videos, ate when I got hungry, and wrote some letters to my family.

Then the rest of the family came back. All of a sudden, Yuntian came running up to say that they wanted waffles. So Hsiu-ling was bustled into her mother’s room on the second floor and the door was shut and locked. Then I was hurried past the door down to the living room where I made waffles. Yuntian ran a plate up to his mom and Hsiu-ling so she could enjoy the new taste treat, too. I played with the nieces and stretched my legs a little until word from the second floor came that Hsiu-ling wanted to come down to watch tv. So I was bustled upstairs again. When I was safely ensconced in my room with the door closed, Hsiu-ling was allowed out of her mother’s room and had the run of most of the house.

For the next few days, the family pretty much stayed all together. No one had to work for the rest of the week, and there were plenty of bedrooms (by their standards) and room on the couches. One of the unmarried girls or Elder Sister would bring the laundry up to the third floor where the washing machine was out in the roof garden, and I would have company while we were doing the laundry. Once the laundry was hung out to dry, my companion would take my dirty dishes downstairs, and I was left in peace to read, watch videos, and snack in my bedroom. I could also go out onto the roof and watch the neighbors. When they wanted waffles, Hsiu-ling would be locked in her mother’s bedroom until the locusts were satisfied. Then I would retreat back up to my lair. The nieces, Pa, and most of the girls would go out every day to a park or for a hike. Finally, Pa and Ma decided that I had been shut away long enough and sent Hsiu-ling and her husband back to home. Elder Sister and her family left that day, too, because they had to visit relatives on Elder Brother-in-law’s side of the family.

When the married girls were gone, Pa and Ma took me to call on the relatives who had come to the wedding. Our first stop was the Liu family homestead up in the hills in Hsinchu County. We visited Pa’s brothers and cousins who were still living in the old family farm compound. I was taken up to visit the family tomb and meet the ancestors. I did not burn incense, but per my agreement with Pa, I did bow my head and pray for the Liu clan at the tomb. Then we went down into Toufen Town to visit Ma’s brothers and mother. We spent the night at Elder Sister’s house because it was quite late by the time we had finished our New Year’s courtesy calls.

The next few days after we had finished visiting the family elders, the family members who were younger than Pa and Ma came to our house to visit. I must have gone through ten pounds of flour because I made fresh batches of waffles every time new visitors came that New Year’s season. Finally, it was time for the Lantern Festival, and the Chinese New Year came to an end. Everyone went back to work. That year, because we had a new house and a new bride, Pa took off more days from work than was his custom. He had more visits to make and more courtesy calls to receive. In later years, he usually only took off a week. By the third year, they had stopped offering the chicken to the ancestors in the middle of the night. But the family dinners and visits to and from friends and relatives is something that continues every year.

At the New Year, working children give their parents gifts of money in red envelopes. Parents also give money to their children and grandchildren. If you are married, you are expected to give to unmarried, younger siblings, to nieces and nephews, and to children of your friends and cousins. Everyone keeps a running tally of how much they have been given by a particular person over the year, and then they try to repay it to the children at the Chinese New Year. (I got much better at mental math after my marriage.)

Even the illiterate women knew exactly how much money had been in every gift envelope given to them throughout the year. They would recite the tally to a child and have the child add up all the debts to figure out how much they owed people on Chinese New Year. It is inauspicious to start the year with debt.

All the unmarried girls and Yuni got to come home for New Year’s Eve dinner. We all ate together at the round dining table. There was a big bowl of fish soup, but we were only supposed to take a taste and leave the rest, so there would be plenty in the New Year. We had red couplets beside the doorway praying for blessings on the household. Yuni and I got one of our friends from church to write them, so they were Christian poems. They were actually quite nice, and Pa Liu was pleased that they were hand-written in nice calligraphy instead of just store-bought ones.

We all went to bed, but Ma and Pa and Hsiu-Mei, Hsiu-Chen, and Yuntian got up in the middle of the night to offer a whole boiled chicken to the ancestors and to set off firecrackers. I was just as happy not to have to get out from under my warm blankets because it was chilly. The next day we all had to wear red, new clothes. I just wore my red wedding dress from the church ceremony because I didn’t want to buy yet another red dress. Yuni wore his suit from the wedding, too. We ate sweet rice cake and fruit and watermelon seeds. Then we all went out to a park for a day at the lake. We were all dressed up for it, too. Then we came home and cleaned up for the next day when the married daughters would come home.

Traditionally, married daughters come home on the second day of the Chinese New Year. Yuni should have taken me to visit my parents, but he was back at his military unit, and it would not have been feasible for me to fly back to the US. So instead, I made waffles for everyone for breakfast. Elder Sister and Elder Brother-in-Law and their four daughters arrived bright and early the next morning. They all loved the waffles. (My relatives had given me a waffle iron for my wedding, and I had a cookbook with a recipe for homemade waffles.) We kept waiting and waiting for Youngest Sister and her husband. Finally, we got a phone call that her mother-in-law was not going to allow her to come unless the Lius guaranteed that she and I would not see each other face to face while she was here.

I knew that the Liu family was worried about her being pregnant with a broken leg, so I said that I would stay upstairs in my third floor rooms. They all thanked me profusely, and I went up to read. Yuntian later came up with a small tv and VCR and a pile of kung-fu movie videos. He also kept bringing food up for me in case I was hungry. I hung over the top of the house and watched her arrive (darting back before anyone saw me, of course.) Since Youngest Sister (Hsiu-ling) had a broken leg she could not go out anywhere. She just sat at home with her mother and one or two of her sisters while her husband and the rest of the entire group took Elder Sister’s children to a park. I unpacked more of my books from America, read Hawaii, watched videos, ate when I got hungry, and wrote some letters to my family.

Then the rest of the family came back. All of a sudden, Yuntian came running up to say that they wanted waffles. So Hsiu-ling was bustled into her mother’s room on the second floor and the door was shut and locked. Then I was hurried past the door down to the living room where I made waffles. Yuntian ran a plate up to his mom and Hsiu-ling so she could enjoy the new taste treat, too. I played with the nieces and stretched my legs a little until word from the second floor came that Hsiu-ling wanted to come down to watch tv. So I was bustled upstairs again. When I was safely ensconced in my room with the door closed, Hsiu-ling was allowed out of her mother’s room and had the run of most of the house.

For the next few days, the family pretty much stayed all together. No one had to work for the rest of the week, and there were plenty of bedrooms (by their standards) and room on the couches. One of the unmarried girls or Elder Sister would bring the laundry up to the third floor where the washing machine was out in the roof garden, and I would have company while we were doing the laundry. Once the laundry was hung out to dry, my companion would take my dirty dishes downstairs, and I was left in peace to read, watch videos, and snack in my bedroom. I could also go out onto the roof and watch the neighbors. When they wanted waffles, Hsiu-ling would be locked in her mother’s bedroom until the locusts were satisfied. Then I would retreat back up to my lair. The nieces, Pa, and most of the girls would go out every day to a park or for a hike. Finally, Pa and Ma decided that I had been shut away long enough and sent Hsiu-ling and her husband back to home. Elder Sister and her family left that day, too, because they had to visit relatives on Elder Brother-in-law’s side of the family.

When the married girls were gone, Pa and Ma took me to call on the relatives who had come to the wedding. Our first stop was the Liu family homestead up in the hills in Hsinchu County. We visited Pa’s brothers and cousins who were still living in the old family farm compound. I was taken up to visit the family tomb and meet the ancestors. I did not burn incense, but per my agreement with Pa, I did bow my head and pray for the Liu clan at the tomb. Then we went down into Toufen Town to visit Ma’s brothers and mother. We spent the night at Elder Sister’s house because it was quite late by the time we had finished our New Year’s courtesy calls.

The next few days after we had finished visiting the family elders, the family members who were younger than Pa and Ma came to our house to visit. I must have gone through ten pounds of flour because I made fresh batches of waffles every time new visitors came that New Year’s season. Finally, it was time for the Lantern Festival, and the Chinese New Year came to an end. Everyone went back to work. That year, because we had a new house and a new bride, Pa took off more days from work than was his custom. He had more visits to make and more courtesy calls to receive. In later years, he usually only took off a week. By the third year, they had stopped offering the chicken to the ancestors in the middle of the night. But the family dinners and visits to and from friends and relatives is something that continues every year.

At the New Year, working children give their parents gifts of money in red envelopes. Parents also give money to their children and grandchildren. If you are married, you are expected to give to unmarried, younger siblings, to nieces and nephews, and to children of your friends and cousins. Everyone keeps a running tally of how much they have been given by a particular person over the year, and then they try to repay it to the children at the Chinese New Year. (I got much better at mental math after my marriage.)

Even the illiterate women knew exactly how much money had been in every gift envelope given to them throughout the year. They would recite the tally to a child and have the child add up all the debts to figure out how much they owed people on Chinese New Year. It is inauspicious to start the year with debt.

Saturday, September 12, 2009

My Life in a Multi-generational Household

The first day of Chinese New Year, 1987

(notice the sausages drying on the 2nd floor)

Ma and Pa Liu and Hsiu-chen in the new living room

In the library/tatami alcove of our third floor bedroom

Ma Liu and Yuntian out on a New Year's excursion

The modern kitchen in our new house.

Liu Yuni was in the army, and he did not have leave after our honeymoon for about five months, except for the first day of the Chinese New Year. After that the most his unit got was “movie nights,” when their officers walked them to a movie theater off-base and took them to the movies. Sometimes the assistant commander would let Liu Yuni take the bus home, as long as he was back in the movie theater before the end of the show. So we got an hour here and there together. I did go to visit him, and since I was now his legal wife, visiting was much easier than it had been. Every Wednesday night, I would take the bus to the base, and his commander would take us to another officer’s house where I would teach four unit commanders English. Liu Yuni was supposed to be learning, too, but I think he was too nervous. The officers had to learn basic conversation because they were taking a language test to be eligible for further military training in the US. Two of the members of my little class passed the test and came to the US for two years training.

Despite the fact that my husband was not home, I was never alone or really lonely. My brother-in-law, Yuntian was in ninth grade. He was fifteen years old. Only two of Liu Yuni’s five sisters were married at that time; Eldest Sister had four daughters and lived with her husband in the town of Toufen. She came up to visit her parents on Sundays once or twice a month. Sometimes Pa Liu would take us all down to Toufen to visit the uncles, and we would wind up at Eldest Sister’s house for dinner. Youngest Sister had been married just a month before our wedding. She was living in the town just north of Chung-li near the airport. She was pregnant and had a broken leg, so we did not see much of her. Furthermore, there was a traditional prohibition that brides could not see one another for the first four months of their marriages. I suspect that this was to prevent jealousy over who was being treated better by their in-laws. When Youngest Sister came home, I would hide upstairs in my apartment on the third floor until she left. After she broke her leg, her husband brought her home for an overnight stay during the Chinese New Year holiday to reassure her parents that everything was all right. Yuntian was charged with bringing me food and renting video tapes for me to watch so I didn’t get bored. Fortunately, my grandmother and aunt had added quite a few of their old paperback bestsellers to my library before I shipped it to Taiwan. One of the books was Hawaii by James Michener. Youngest Sister’s stay was only supposed to be one night and two days, but she was so sad and lonely (and she was barely sixteen) that she wound up staying for three nights and four days. She would have stayed on with us indefinitely, but Pa and Ma Liu told her that she was not being fair to me. They shipped her back to her in-law’s place, and I was released from my rooms on the third floor.

Second Sister Hsiu-Mei worked in Eldest Sister’s lampshade factory. She was home on holidays, but for the most part she lived with Eldest Sister in Toufen. Third Sister Hsiu-chiu worked for Pa Liu’s construction company by day and went to night high school in the evenings. Fourth Sister Hsiu-chen worked in a factory at the nearby industrial park. She had a space in the company dormitory and usually only came home on her days off or on holidays or when she wanted to do laundry.

In a typical day, we all got up early. Ma Liu made a full Chinese meal with meat and vegetables and rice for breakfast because three of them did construction work. She cooked in pork lard, and my stomach could not take it. I started getting sick in the mornings until I began buying buns for my breakfast near the train station. We would all go to work or school in the mornings. Yuntian came home first in the afternoons. In the old house, he would split kindling for the wood-burning water heater. In the new house, he did not have to do this chore because all the water heaters were gas burning. He did his homework in front of the tv. Because I taught evening classes, Ma Liu and Hsiu-chiu cooked dinner on week nights. I cooked and cleaned the house on the weekends. After dinner, Ma and Hsiu-chiu did the laundry. I would do the dishes and clean up the kitchen on week nights after I ate a late dinner when I got home.

Every pay day, the unmarried girls, who worked outside the family business, would bring money home to Ma for groceries and household use. All the proceeds from Ma and Hsiu-chiu’s labor went to paying off the debts. I was responsible for paying the mortgage and giving a certain amount to Ma for groceries. Not long into the marriage, I realized that I needed to find higher paying jobs. The budget was so tight that Ma had to ask me for money so Yuntian could pay his fees for school spring semester. That first year of the marriage, everyone was entirely focused on paying off the family’s debt. I asked around among friends from church in Chung-li and found a job teaching English at a “cram” school there. It paid very well, better than the schools in Taipei, and I got home much earlier. In the spring, I was referred to the local university to teach English conversation in their College of Business. That job didn’t start until fall, but I was given a position as part-time English secretary to the President that started over the summer. Eventually, I stopped going to Taipei and worked only near my home in Chung-li. Within six or seven months, I was earning as much as my father-in-law’s contracting business every month. I took over paying most of the household expenses, allowing the rest of the family to dedicate almost all their earnings to paying off the debt. We all worked six days a week. I usually taught classes in the evenings, so I was not at home too much.

Sunday afternoon was free time. Pa would take us out to a park or to hike in nearby mountains on nice days. Or sometimes he would just sit in the living room eating watermelon seeds while he and Ma told us stories about their life before modern conveniences. It was fascinating for me to learn all the changes that they had seen in a life-time. They would ask me about life in America. When Ma could not understand me or when I could not understand her, Pa and his children would translate between Hakka and Mandarin. Liu Yuntian liked to watch kung-fu movies, so we would usually rent videos on the weekend and watch them.

We got along quite well for several reasons. First, we had a focus; we were working as a team to get the family out of debt. Second, we knew that we were coming from very different backgrounds, so we cut each other a lot of slack in our day-to-day dealings with each other. I did some things that were normal for Americans but were very rude in the traditional culture. The Lius didn’t say anything because they knew I was not doing them out of spite, but out of ignorance. After a long while had past, when no one was angry any more, Hsiu-chiu would explain to me the Hakka way of doing things. I tried to adjust myself. If it was something I really couldn’t do, I would talk to Pa and explain my point of view. He would consider things, and usually we found a position of compromise. In general, everyone treated everyone else with courtesy and respect.

Despite the fact that my husband was not home, I was never alone or really lonely. My brother-in-law, Yuntian was in ninth grade. He was fifteen years old. Only two of Liu Yuni’s five sisters were married at that time; Eldest Sister had four daughters and lived with her husband in the town of Toufen. She came up to visit her parents on Sundays once or twice a month. Sometimes Pa Liu would take us all down to Toufen to visit the uncles, and we would wind up at Eldest Sister’s house for dinner. Youngest Sister had been married just a month before our wedding. She was living in the town just north of Chung-li near the airport. She was pregnant and had a broken leg, so we did not see much of her. Furthermore, there was a traditional prohibition that brides could not see one another for the first four months of their marriages. I suspect that this was to prevent jealousy over who was being treated better by their in-laws. When Youngest Sister came home, I would hide upstairs in my apartment on the third floor until she left. After she broke her leg, her husband brought her home for an overnight stay during the Chinese New Year holiday to reassure her parents that everything was all right. Yuntian was charged with bringing me food and renting video tapes for me to watch so I didn’t get bored. Fortunately, my grandmother and aunt had added quite a few of their old paperback bestsellers to my library before I shipped it to Taiwan. One of the books was Hawaii by James Michener. Youngest Sister’s stay was only supposed to be one night and two days, but she was so sad and lonely (and she was barely sixteen) that she wound up staying for three nights and four days. She would have stayed on with us indefinitely, but Pa and Ma Liu told her that she was not being fair to me. They shipped her back to her in-law’s place, and I was released from my rooms on the third floor.

Second Sister Hsiu-Mei worked in Eldest Sister’s lampshade factory. She was home on holidays, but for the most part she lived with Eldest Sister in Toufen. Third Sister Hsiu-chiu worked for Pa Liu’s construction company by day and went to night high school in the evenings. Fourth Sister Hsiu-chen worked in a factory at the nearby industrial park. She had a space in the company dormitory and usually only came home on her days off or on holidays or when she wanted to do laundry.

In a typical day, we all got up early. Ma Liu made a full Chinese meal with meat and vegetables and rice for breakfast because three of them did construction work. She cooked in pork lard, and my stomach could not take it. I started getting sick in the mornings until I began buying buns for my breakfast near the train station. We would all go to work or school in the mornings. Yuntian came home first in the afternoons. In the old house, he would split kindling for the wood-burning water heater. In the new house, he did not have to do this chore because all the water heaters were gas burning. He did his homework in front of the tv. Because I taught evening classes, Ma Liu and Hsiu-chiu cooked dinner on week nights. I cooked and cleaned the house on the weekends. After dinner, Ma and Hsiu-chiu did the laundry. I would do the dishes and clean up the kitchen on week nights after I ate a late dinner when I got home.

Every pay day, the unmarried girls, who worked outside the family business, would bring money home to Ma for groceries and household use. All the proceeds from Ma and Hsiu-chiu’s labor went to paying off the debts. I was responsible for paying the mortgage and giving a certain amount to Ma for groceries. Not long into the marriage, I realized that I needed to find higher paying jobs. The budget was so tight that Ma had to ask me for money so Yuntian could pay his fees for school spring semester. That first year of the marriage, everyone was entirely focused on paying off the family’s debt. I asked around among friends from church in Chung-li and found a job teaching English at a “cram” school there. It paid very well, better than the schools in Taipei, and I got home much earlier. In the spring, I was referred to the local university to teach English conversation in their College of Business. That job didn’t start until fall, but I was given a position as part-time English secretary to the President that started over the summer. Eventually, I stopped going to Taipei and worked only near my home in Chung-li. Within six or seven months, I was earning as much as my father-in-law’s contracting business every month. I took over paying most of the household expenses, allowing the rest of the family to dedicate almost all their earnings to paying off the debt. We all worked six days a week. I usually taught classes in the evenings, so I was not at home too much.

Sunday afternoon was free time. Pa would take us out to a park or to hike in nearby mountains on nice days. Or sometimes he would just sit in the living room eating watermelon seeds while he and Ma told us stories about their life before modern conveniences. It was fascinating for me to learn all the changes that they had seen in a life-time. They would ask me about life in America. When Ma could not understand me or when I could not understand her, Pa and his children would translate between Hakka and Mandarin. Liu Yuntian liked to watch kung-fu movies, so we would usually rent videos on the weekend and watch them.

We got along quite well for several reasons. First, we had a focus; we were working as a team to get the family out of debt. Second, we knew that we were coming from very different backgrounds, so we cut each other a lot of slack in our day-to-day dealings with each other. I did some things that were normal for Americans but were very rude in the traditional culture. The Lius didn’t say anything because they knew I was not doing them out of spite, but out of ignorance. After a long while had past, when no one was angry any more, Hsiu-chiu would explain to me the Hakka way of doing things. I tried to adjust myself. If it was something I really couldn’t do, I would talk to Pa and explain my point of view. He would consider things, and usually we found a position of compromise. In general, everyone treated everyone else with courtesy and respect.

Saturday, September 5, 2009

The Hakka

Before I get too far into the narrative of my life as a white Chinese daughter-in-law, I need to tell you about the Hakka. The Liu family are Hakka speakers. The Hakka are a linguistic minority of the Han Chinese. Their tradition says that they were nobility from the Yellow River valley that fled South before barbarian invasions throughout the centuries. There are pockets of Hakka speakers in China scattered throughout the mountainous areas of Sichuan, Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong Provinces on the mainland. Later waves of Hakka migrated out of the coastal provinces of Fujian and Guangdong to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, Hawaii, and the rest of the world. Legend has it that Kuala Lumpur was founded by a Hakka-speaking business leader.

According to their oral tradition, the Hakka strictly adhere to the Confucian code and traditional ancestor worship. Their language and customs preserve the oldest of Chinese traditions. The word Hakka means “guest people”. And since they are perpetual sojourners, bereft of their true ancestral homes, their women never had to bind their feet. Hakka women are traditionally strong, and if they industriously earn money for the clan, they are treated as equals with the men. This fact caused many of my friends from other linguistic sub-groups to fear for me because I would be expected to work harder than in other Chinese sub-cultures. Teacher Chin thought I would have an easier time of it because the Hakka are also known for their fairness and straight-speaking. She knew I was not afraid of hard work and felt that this was a good match for my temperament.

The rest of this post is a series of quotes from James Michener’s epic book Hawaii. He gets most of the legend right, and it is quite cool that the ethnic story of my family by marriage was featured in a best-selling novel by one of my favorite authors.

In the year 817 … the northern sections of China were ravaged by an invading horde of Tartars whose superior horsemanship, primitive moral courage and lack of hesitation in applying brute force quickly overwhelmed the more sophisticated Chinese … The effect of the invasion fell most heavily upon the great Middle Kingdom, the heartland of China, for it was these lush fields and rich cities that the Tartars sought, so toward the middle of the century they dispatched an army southward to invade Honan Province … In Honan at this time there lived a cohesive body of Chinese known by no special name, but different from their neighbors. They were taller, more conservative, spoke a pure ancient language uncontaminated by modern flourishes, and were remarkably good farmers. (p. 373)

As [the] resolute group moved south from Honan Province they acquired people from more than a hundred additional villages whose sturdy peasants … refused to accept Tartar domination. In time, what had started as a rabble became in actuality a solid army … The years passed, and this curious, undigested body of stalwart Chinese, holding to old customs and disciplined as no other that had ever wandered across China, probed constantly southward, until in the year 874 they entered upon a valley in Kwangtung Province, west of the city of Canton. It had a clear, swift-running river, fine mountains to the rear, and soil that seemed ripe for intensive cultivation. (p. 382-383)

Finally, when military occupation of the entire valley proved unfeasible, [they] decided to leave the lowlands to the southerners and to occupy all the highlands … and in time the highlanders became known as the Hakka, the Guest People, while the lowlanders were called the Punti, the natives of the Land.

According to their oral tradition, the Hakka strictly adhere to the Confucian code and traditional ancestor worship. Their language and customs preserve the oldest of Chinese traditions. The word Hakka means “guest people”. And since they are perpetual sojourners, bereft of their true ancestral homes, their women never had to bind their feet. Hakka women are traditionally strong, and if they industriously earn money for the clan, they are treated as equals with the men. This fact caused many of my friends from other linguistic sub-groups to fear for me because I would be expected to work harder than in other Chinese sub-cultures. Teacher Chin thought I would have an easier time of it because the Hakka are also known for their fairness and straight-speaking. She knew I was not afraid of hard work and felt that this was a good match for my temperament.

The rest of this post is a series of quotes from James Michener’s epic book Hawaii. He gets most of the legend right, and it is quite cool that the ethnic story of my family by marriage was featured in a best-selling novel by one of my favorite authors.

In the year 817 … the northern sections of China were ravaged by an invading horde of Tartars whose superior horsemanship, primitive moral courage and lack of hesitation in applying brute force quickly overwhelmed the more sophisticated Chinese … The effect of the invasion fell most heavily upon the great Middle Kingdom, the heartland of China, for it was these lush fields and rich cities that the Tartars sought, so toward the middle of the century they dispatched an army southward to invade Honan Province … In Honan at this time there lived a cohesive body of Chinese known by no special name, but different from their neighbors. They were taller, more conservative, spoke a pure ancient language uncontaminated by modern flourishes, and were remarkably good farmers. (p. 373)

As [the] resolute group moved south from Honan Province they acquired people from more than a hundred additional villages whose sturdy peasants … refused to accept Tartar domination. In time, what had started as a rabble became in actuality a solid army … The years passed, and this curious, undigested body of stalwart Chinese, holding to old customs and disciplined as no other that had ever wandered across China, probed constantly southward, until in the year 874 they entered upon a valley in Kwangtung Province, west of the city of Canton. It had a clear, swift-running river, fine mountains to the rear, and soil that seemed ripe for intensive cultivation. (p. 382-383)

Finally, when military occupation of the entire valley proved unfeasible, [they] decided to leave the lowlands to the southerners and to occupy all the highlands … and in time the highlanders became known as the Hakka, the Guest People, while the lowlanders were called the Punti, the natives of the Land.

It was in this manner that one of the strangest anomalies of history developed, for during a period of almost a thousand years these two contrasting bodies of people lived side by side with no friendly contact. The Hakka lived in the highlands and farmed; the Punti lived in the lowlands and established an urban life … The upland people, the Hakka preserved intact their ancient habits inherited from the purest fountain of Chinese culture … The second difference was … the self-reliant Hakka women refused to bind the feet of their girl babies … Hakka girls were known to make powerful, strong-willed, intelligent wives who demanded an equal voice in family matters. (p. 384-385)

--Hawaii, by James Michener

--Hawaii, by James Michener

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)