With our washer and dryer, notice that they're made of plastic to minimize rusting. The washer has a spinner on one side that is separate from the washing drum.

On the East Coast of Taiwan with ship in background

Life with the Lius was very different from anything I had ever experienced. Their family structure was much more traditional than the families I had lived with in Taipei. They were a real country family, who had just moved to the city less than ten years before our marriage. All the children and Pa Liu knew Mandarin, but Ma Liu only spoke Hakka, and most of the time the family spoke Hakka at home. I was back in an environment where I understood nothing, and I did not have a Teacher Chin to help me out.

Pa Liu had decided that since I had already learned Mandarin from English, which was a harder task, Ma Liu would learn Mandarin from Hakka. Hsiu-chiu, Yuntian, and I set to work teaching her. Ma Liu is extremely bright, and despite the fact that she was over 50, she quickly picked up the language. She had been with her own mother in the hospital when her mother had had surgery. Neither of them spoke Mandarin, so they could not communicate with the doctors and nurses. It had been a terrible, frightening time for Ma, and she was determined to learn the national language.

I continued to work at the publishing company and an evening English school in Taipei for the first few months of my marriage. I would take the bus to the train station in the mornings, but at night, I was often coming home around eleven, so Pa Liu or Yuntian would be waiting at the train station to pick me up.

Usually there is a certain amount of hazing that goes on when a new woman joins a traditional family. The younger sisters did that a little. I would come home late at night to a sink full of dishes or have to spend my weekends doing all the cleaning. But since I was contributing more money to the family coffers than they were, Ma and Pa Liu quickly put a stop to that. The girls resented it a little, but I determined to pull my weight with the household chores on the days that I didn’t go to Taipei. When they saw that I was not lazy or snooty, they warmed up to me, and we all got along quite well. My sisters-in-law took turns translating family conversations for me, so I would understand the Hakka.

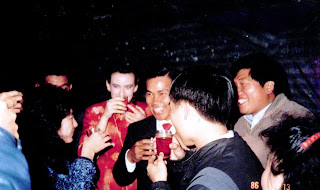

Life was pretty good in the nuclear family, but when we had events with the whole clan, things were a little bit more complicated. We moved into the new house just before the Chinese New Year in 1987. So of course, we had to have a big feast. This time, Ma Liu and her daughters and I made all the food for just a small intimate gathering of their closest relatives, about forty guests. Then for the next few months, other family members who had not attended the feast would drop in for dinner bearing housewarming gifts. And they all wanted to know when my baby was due.

This made things a little awkward because there was a missile crisis with mainland China, and Liu Yuni didn’t get any leave for five months after the wedding. The old aunties kept coming and prodding my stomach to feel the baby inside, which wasn’t there… Finally, one day I lost it and told my sister-in-law to tell them in Hakka that we hadn’t had a proper wedding night, we had “lightbulbs” along on the honeymoon, and Liu Yuni hadn’t been home since. If there was a baby in there, then the Liu family should be worried because I wasn’t pregnant at the wedding. Well, that direct little American outburst shocked them into silence. Then I got a reputation among the women of having a bad temper. I guess that wasn’t a bad thing. They stopped poking my stomach and started going to temples to pray that Liu Yuni would get leave so my mother-in-law would have a grandbaby soon. One day when we were alone in the kitchen with my mother-in-law’s favorite daughter, she told me via translation that most of Liu Yuni’s cousins had been pregnant before their wedding nights. So the old aunties just assumed that it was the same for me. After all, if you weren’t pregnant, why would you possibly want to get married? The pressure on me to produce an heir was tremendous.

Pa Liu had decided that since I had already learned Mandarin from English, which was a harder task, Ma Liu would learn Mandarin from Hakka. Hsiu-chiu, Yuntian, and I set to work teaching her. Ma Liu is extremely bright, and despite the fact that she was over 50, she quickly picked up the language. She had been with her own mother in the hospital when her mother had had surgery. Neither of them spoke Mandarin, so they could not communicate with the doctors and nurses. It had been a terrible, frightening time for Ma, and she was determined to learn the national language.

I continued to work at the publishing company and an evening English school in Taipei for the first few months of my marriage. I would take the bus to the train station in the mornings, but at night, I was often coming home around eleven, so Pa Liu or Yuntian would be waiting at the train station to pick me up.

Usually there is a certain amount of hazing that goes on when a new woman joins a traditional family. The younger sisters did that a little. I would come home late at night to a sink full of dishes or have to spend my weekends doing all the cleaning. But since I was contributing more money to the family coffers than they were, Ma and Pa Liu quickly put a stop to that. The girls resented it a little, but I determined to pull my weight with the household chores on the days that I didn’t go to Taipei. When they saw that I was not lazy or snooty, they warmed up to me, and we all got along quite well. My sisters-in-law took turns translating family conversations for me, so I would understand the Hakka.

Life was pretty good in the nuclear family, but when we had events with the whole clan, things were a little bit more complicated. We moved into the new house just before the Chinese New Year in 1987. So of course, we had to have a big feast. This time, Ma Liu and her daughters and I made all the food for just a small intimate gathering of their closest relatives, about forty guests. Then for the next few months, other family members who had not attended the feast would drop in for dinner bearing housewarming gifts. And they all wanted to know when my baby was due.

This made things a little awkward because there was a missile crisis with mainland China, and Liu Yuni didn’t get any leave for five months after the wedding. The old aunties kept coming and prodding my stomach to feel the baby inside, which wasn’t there… Finally, one day I lost it and told my sister-in-law to tell them in Hakka that we hadn’t had a proper wedding night, we had “lightbulbs” along on the honeymoon, and Liu Yuni hadn’t been home since. If there was a baby in there, then the Liu family should be worried because I wasn’t pregnant at the wedding. Well, that direct little American outburst shocked them into silence. Then I got a reputation among the women of having a bad temper. I guess that wasn’t a bad thing. They stopped poking my stomach and started going to temples to pray that Liu Yuni would get leave so my mother-in-law would have a grandbaby soon. One day when we were alone in the kitchen with my mother-in-law’s favorite daughter, she told me via translation that most of Liu Yuni’s cousins had been pregnant before their wedding nights. So the old aunties just assumed that it was the same for me. After all, if you weren’t pregnant, why would you possibly want to get married? The pressure on me to produce an heir was tremendous.