On November 2, 3, and 4, I helped China Aid Association in my capacity as a free-lance Chinese-English translator/interpreter. They had brought a group of six human rights lawyers from China to testify before the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission. The lawyers then flew to California to attend a symposium on stopping religious violence at Pepperdine University. They also had meetings with Pepperdine faculty and gave a presentation to the students at Pepperdine Law School. I was one of the interpreters for those functions. On their way out of town several of the lawyers, including Jiang Tianyong (see below), came to Cal State Long Beach and spoke with one of our International Studies classes about internet freedom, human rights issues, and democracy in China.

These lawyers all said that China has great laws on paper, but the laws are not enforced in favor of the people. The lawyers work to ensure that members of any religion or people in freedom of speech cases have legal representation. The lawyers themselves pay a big price to to this. Jiang Tianyong is a Christian; he has defended many Christians in house churches. He also helped defend the so-called "Living Buddha" in Sichuan last year, and he frequently takes on Falun Gong cases because the government is so anti-Falun Gong that almost no lawyers will defend the accused in such cases. The lawyers take these cases because they believe that the only hope for China is adherence to "rule of law."

The rest of this post is copied from the China Aid website. If you go to the website at

www.chinaaid.org, you will see another article about other lawyers from the group who were interrogated and placed under surveillance. You can also access the audio files of the testimony before the Human Rights Commisson.

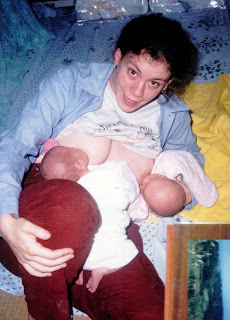

Chinese human rights lawyer Jiang Tianyong and one of my interpretation clients.

Chinese human rights lawyer Jiang Tianyong and one of my interpretation clients.

Chinese Human Rights Attorney Jiang Tianyong Arrested and His Wife Beaten in Front of Their Daughter

Attorney Jiang Tianyong recently returned from a tour in the US exposing the abusive treatment of human rights lawyers in China.

ChinaAid

BEIJING--At 7:40 AM (Beijing time) on Nov. 19, Jiang Tianyong and his wife attempted to leave their home to take their daughter to school, when they were barred from leaving the apartment building by Public Security Bureau officers assembled at the gate. Before Jiang could speak with them, four officers grabbed him violently and forced him into a police car. A police officer named Wang Tao threw his wife to the ground and began striking her. Jiang's 7-year-old daughter cried helplessly as she watched her father being dragged away to detention by the officers.

Jiang Tianyong was arrested and held in detention at the Yangfangdian PSB office of Haidian District, Beijing for over 13 hours, under the guard of Officers Li Aimin and Wang Tao. He was allowed only one meal during his detention. A dozen human rights lawyers rallied in front of the station to demand Jiang's release and to show support for their colleague. He was released at 9:26 PM (Beijing time) to return home to his family.

Immediately after learning of Jiang's arrest, ChinaAid contacted the US Embassy in Beijing and several U.S. Congressional offices, notifying them of Jiang Tianyong's brutal treatment and detention. A US Embassy official quickly responded and said that the Embassy had called the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and formally registered the U.S. Government's concern and opposition to this action. The embassy further reported the incident to the National Security Council and the State Department, all prior to Jiang's release.

Jiang Tianyong had just returned to Beijing on Tuesday, November 17, after touring the United States for 4 weeks and speaking out on the unjust treatment of human rights lawyers in China. On several occasions, he and the other five Chinese human rights defenders on the tour advised U.S. officials to encourage President Obama to meet with human rights lawyers and speak out on religious freedom while visiting China.

Read Jiang Tianyong's Testimony before the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission. Hear his remarks at the National Press Club and at the hearing in Washington, DC.

Fearing the lawyers would become targets upon their return, Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission co-chair Frank Wolf of Virginia warned against ill-treatment upon the lawyers' return: "If any of them are arrested or harrassed when they get back, I will do everything I can to just create the biggest problem possible for the Obama adminsitration and for the Chinese government." Yesterday, on November 18, Jiang Tianyong and a fellow legal researcher attempted to arrange a meeting with President Obama before he left China, hoping to follow through with the lawyers' request for US acknowlegement of the current dire situation. After receiving a phone call from the U.S. Embassy, informing him President Obama would not be able to meet with the group of five human rights lawyers who had gathered, 200 police officers immediately pulled up, and interrogated Jiang and one of his colleagues in the hotel for over an hour. They were informed they "were not allowed to meet President Obama" and would "be held until he left" yesterday afternoon.The brutal assault of Jiang Tianyong, his wife, and their daughter is an unjust an inexcusable attack on the rights of peaceful Chinese citizens. Jiang's family now suffers even more from this abuse, as their well-being was taxed after Jiang's license to practice law was revoked and his tenure at the Beijing Global Law Firm was terminated in April of this year. ChinaAid denounces the cruel and inhumane treatment of human rights Attorney Jiang Tianyong. We urge the Chinese authorities to stop their harassment of Attorney Jiang and the other human rights lawyers and their families who have been detained during President Obama's visit.

ChinaAid further calls on the international community to pray for healing from this unjust persecution, in the wake of Jiang's courageous tour in the United States, and to call on American leaders to voice their opposition to human rights abuses in China.

EDITOR'S NOTE OF CORRECTION: In our e-mail to our ChinaAid subscribers sent this morning, we reported that Jiang Tianyong was beaten and then dragged away by four police officers. This information was taken from our Chinese media contact in Beijing who misinterpreted the events. Jiang Tianyong was violently seized and forced into a police car, but was not beaten. His wife was beaten by Officer Wang Tao in front of their 7-year-old daughter. We apologize for the mis-report, and will continue to offer breaking news of the events as they transform.

Raise your concerns on Jiang's behalf to the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C.;

Ambassador Zhou Wenzhong

3505 International Place, NW, Washington, D.C. 20008

Tel: (202) 495-2000Fax: (202) 588-9760

Chinese Embassy Press Secretary Baodong, Tel: 202-495-2218

NOTE: If you are a citizen of another country, please click here to find the contact information of the Chinese embassy in your own nation

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb/zwjg/2490/ChinaAid grants permission to reproduce photos and/or information for non-fundraising purposes, with the provision that www.ChinaAid.org is credited. Please contact: Annee@ChinaAid.org with questions or requests for further information.